Imagine this: you’re a child who’s just woken up to more snow than you’ve ever seen in your life. You join your equally exuberant friends and siblings for a fun-packed morning of snowball fights, snowman building and ice sliding… only to then hear a mysterious voice, apparently coming from a snowdrift.

“Hello?” it quivers. You inch nearer to where the sound has come from and spot something round protruding from the snow. It’s a shrivelled, almost frozen head, nearly as white as the surrounding snow, with long, thick icicles spearing from its whiskers like stalactites… did it just move?

“Hello?” says the same trembling voice, as the creature starts to emerge with its hair a ball of ice, one of its fingers resembling a dead stick, and with deeply bloodshot eyes. “I’m lost – can you help me?”

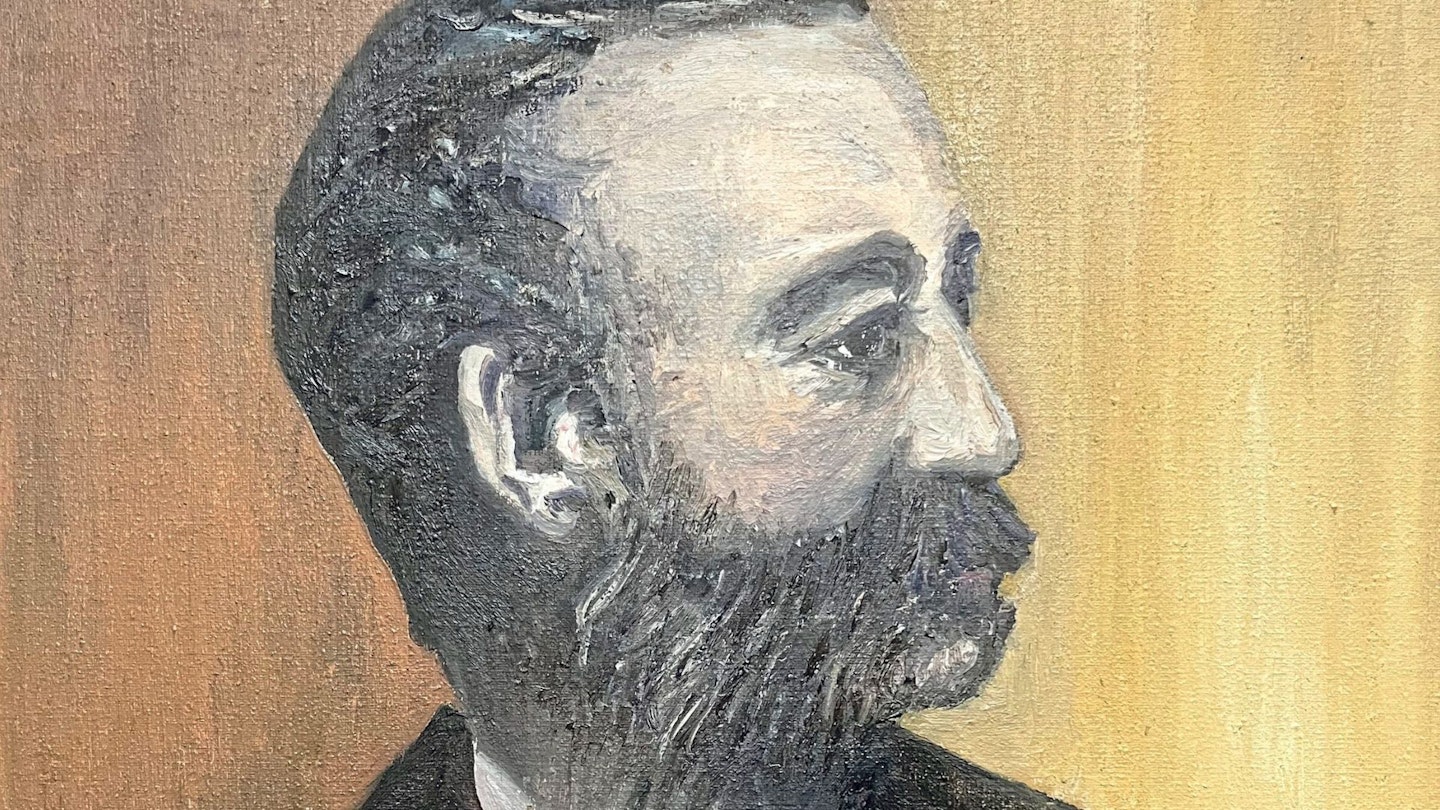

At this point you would probably do exactly what the children did in this very circumstance on 30th January 1865. That is to turn and run, too terrified to scream. They might have thought it was some kind of snow demon, but it was actually Reverend Edmund Donald Carr. And it’s fair to say, he’d just had quite a night of it.

Rev Carr lived in the village of Woolstaston, a few miles north of Church Stretton in the Shropshire Hills. He served the village, plus a nearby hamlet called Ratlinghope. After his Sunday morning service in Woolstaston, he would ride on horseback to Ratlinghope for his 3pm service.

It was a journey of four miles, but with one catch: it involved crossing the Long Mynd, a high, broad moorland plateau with views stretching as far as Snowdonia in fine weather. When the weather closes in, however, it can become an unsettling, disorientating place, and the weather was about to close in on Rev Carr more spectacularly than he could ever have feared.

On Sunday 29th January 1865 he set off for Ratlinghope after a week that had already produced the most snow for more than 50 years. It was too much for the horses. “The drifts were so deep against the hedges and gates, that the poor animals became imbedded in them,” Carr wrote in an account of his experience called A Night in the Snow.

The conditions didn’t deter Carr – he’d crossed the Long Mynd thousands of times before, and he knew that today he needed to go on foot. After negotiating the highest drifts on hands and knees, he made to Ratlinghope, just a few minutes late for his afternoon service. Success… or so he thought.

A hundred and sixty years later, I stand outside the same little church where the reverend preached that frozen afternoon. The building has a small wooden bell tower and a churchyard with half a dozen ancient yews whose stout trunks resemble bundles of sticks. Cloud drifts over the rounded hilltops either side. In the shelter of the valley, the only sounds are chirruping sparrows and chaffinches.

It's an appropriate day to be here, as a chill hangs in the air. The sort that seeps through your skin and clutches your bones. It’s a hard one to shake off, even when on the move. I’m following the footsteps of the vicar’s return journey to Woolstaston… and I will not be ending up in Woolstaston. While Carr was giving his Ratlinghope sermon a vicious gale started blowing in from the east. But the single-minded vicar was determined to get back to his home village in time for a six o’clock sermon.

Fortunately for me, there is no such gale today. I’m grateful to the ascent for warming my bones again. I soon leave farmland for moorland. This was the point where Carr realised he was up against a blizzard with a ferocity he’d never encountered before.

“The force of the wind was most extraordinary,” he recalled.

“I have been in many furious gales, but never in anything to compare with that, as it took me off my legs, and blew me flat down upon the ground over and over again. The sleet too was most painful, stinging one's face and causing such injury to the eyes, that it was impossible to lift up one's head.”

I pass a lone tree sitting on the moor. Arched over as if with a heavy load on its back, its windswept appearance offers a clue as to how wild the conditions can become here. Just beyond the tree is a small herd of ponies. In this environment they look wild, but are not. Small, docile and graceful, they all look fit and well fed, unlike their predecessors back in the winter of 1865.

The carcass of one of these ponies provided the first of three landmarks that should have seen Carr safely home, having passed the same animal on his outward journey. The second landmark was a pool, by which he stopped for a short rest before embarking on the final climb to the top.

I reach the same body of water – Wildmoor Pool – which today is mostly frozen over. The surrounding ground is hard, with a tiny dusting of snow powder spread evenly like icing sugar. From the pool, the land rises on three sides, each way involving an almost identical climb over heather. For me, route finding is easy – an icy lane leads to the summit plateau of the Long Mynd. If a track existed in January 1865, it would have been obscured by the thick duvet of snow. Any direction climbed would have felt like any other. And this is where things began to go desperately wrong for Carr.

The final landmark he was looking for was a patch of fir trees at the start of the descent. The trees were just a few hundred yards away, and from there, he would be able to make it home. But he never reached those trees. Instead, a loss of bearings, not helped by a change in wind direction, led him almost 90 degrees off course.

I reach a lonely signpost at the top of the Long Mynd. It suggests I’m over halfway to Woolstaston, but having reached the cloudline, visibility has become limited. I can’t complain though – the reverend had it considerably worse.

“The storm now came on, if possible, with increased fury,” wrote Carr.

“It was quite impossible to look up or see for a yard around, and the snow came down so thick and fast that my servant, who had come some distance up the lane from Woolstaston in hopes of seeing something of me, describing it to me afterwards, said, "sir, it was just as if they were throwing it on to us out of buckets”.”

Crawling through waist-deep powder in rapidly fading light, Carr was about to fall victim to the Long Mynd’s topography. For although its western slopes are fairly benign, the eastern ones and scarred by deep ravines. With no visibility, he plunged into one of these ravines, hurtling down the hillside headfirst on his back. He managed to stop his rapid descent by digging his feet into the snow.

“My position was anything but agreeable even then, hanging head downwards on a very steep part, and never knowing any moment but what I might start again.”

He tried to descend carefully to the base of the ravine and follow the waterway down to safety, but here the snow was packed 20ft high, and navigating this wasn’t possible.

“I had to face the awful fact that I was lost among the hills, should have to spend the night there, and that, humanly speaking, it was almost impossible that I could survive it.”

I veer south from the lane along the summit plateau, heading to the ravine where Carr ended up. His route was far more complex than mine, and he believed he may have travelled a further three miles south before returning north, continually falling into, and climbing out of, ravines. I keep to the base of a deep gully, carefully negotiating a path of ice sheets, while large icicles hover over the chattering stream next to me.

I doubt whether path or stream sees a ray of sunlight at this time of year, as the hills around me are seriously steep – not the sort you’d want to fall down. I’m also amazed at how much rock cuts its way out of the hillside. It’s ironic that the deep snow – the very thing that caused so many problems for the vicar that night – would almost certainly have saved his life, cushioning his many falls in this precipitous terrain.

On one fall he lost his warm fur gloves, making his hands totally numb and virtually useless. He was also weighed down by “…masses of ice which had formed upon my whiskers, and which were gradually developed into a long crystal beard, hanging half-way to my waist.”

He suffered such extreme hunger that he considered eating the dog skin gloves that remained on his hands, and he became so exhausted that he was falling every two or three steps, each time somehow overcoming the irresistible urge to give in.

“I endeavoured to keep constantly before me the certain fact, that if sleep once overcame me I should never wake again in this life.”

When daylight returned he realised he had become snow-blinded, and at one point jumped on to what he thought was an ice‑covered pool, but was in fact empty space, ultimately landing in a snow drift. On my icy but, thankfully, snow-free descent of the ravine, the sound of gushing water becomes louder. I climb a boulder off the path to peer down the first of two drops that make up Light Spout Waterfall.

Carr, of course, fell over the first drop. His footprints revealed that he then walked right to the edge of the larger second drop that would surely have killed him, then wandered round in circles trying to find a way out. Standing here and seeing the extent and gradient of the rock that rises each side of the falls, I can’t imagine how he could have prised himself out of such a hollow.

As he continued his seemingly endless crawling, tentative stepping, and tumbling, he lost both his boots. But by now his feet were so numb he couldn’t even feel the gorse bushes over which he stomped. I have a far easier escape of the deep narrow gully via a fine path which joins the much larger Carding Mill Valley, with its agreeably flat and relatively broad valley floor.

Coincidentally, I hear the sound of children playing as I continue downstream. It’s a common sound at Carding Mill Valley – one of the family hotspots of the Shropshire Hills – and is always a pleasant one. But to Carr’s ears it would have been music finer than any symphony or concerto ever composed. And although he proceeded to terrify the youngsters with his alarming appearance, one little girl was brave enough to approach him as he stepped out from the snowdrift.

Somehow, she recognised who he was, and the other kids reemerged from their hiding places and helped him indoors, where he was fed tea, bread and butter. Most people, I think, would have taken this opportunity to sleep, perhaps for the rest of the day, knowing that they were now safe and warm. But instead, Rev Carr hung around for a grand total of 15 minutes before continuing to the village of Church Stretton, by which time he had been walking almost non-stop for 22 hours.

From there, he took a horse and cart back towards Woolstaston, having to complete the final few miles on foot. On the way, he met a messenger carrying letters declaring that the Reverend Carr was lost with no hope of survival. One can only imagine the disbelief on the faces of his fellow villagers when he finally made it back.

One of the great appeals of the Shropshire Hills is that, while pleasing to the eye in a green, cheerful, shapely way, there appears to be nothing to fear. But behind the patchwork paddocks, broad green paths and placid ponies, there’s a moodiness to the place that I like. And though I’ll never want to face the sort of conditions experienced by Rev Carr, I enjoy the exciting edge that this moodiness offers – knowing that a foggy curtain can come down on my gentle jaunt to suddenly test my navigation on an enormous plateau bereft of features.

It’s a fantastic heather-clad desert, a place of open space and silence, and it’s wilder than you might think… it’s certainly wilder than Reverend Carr thought it was, and he’d crossed it more than two thousand times.