Pinpoint navigation isn’t easy. In fact, it can be incredibly difficult. Especially if you’re aiming for a precise 10-figure grid reference, zooming in on a location of 1-metre by 1-metre. If you’re handy with a map and compass this may be something you can pull off without the need for technology, but for many of us that isn’t the case.

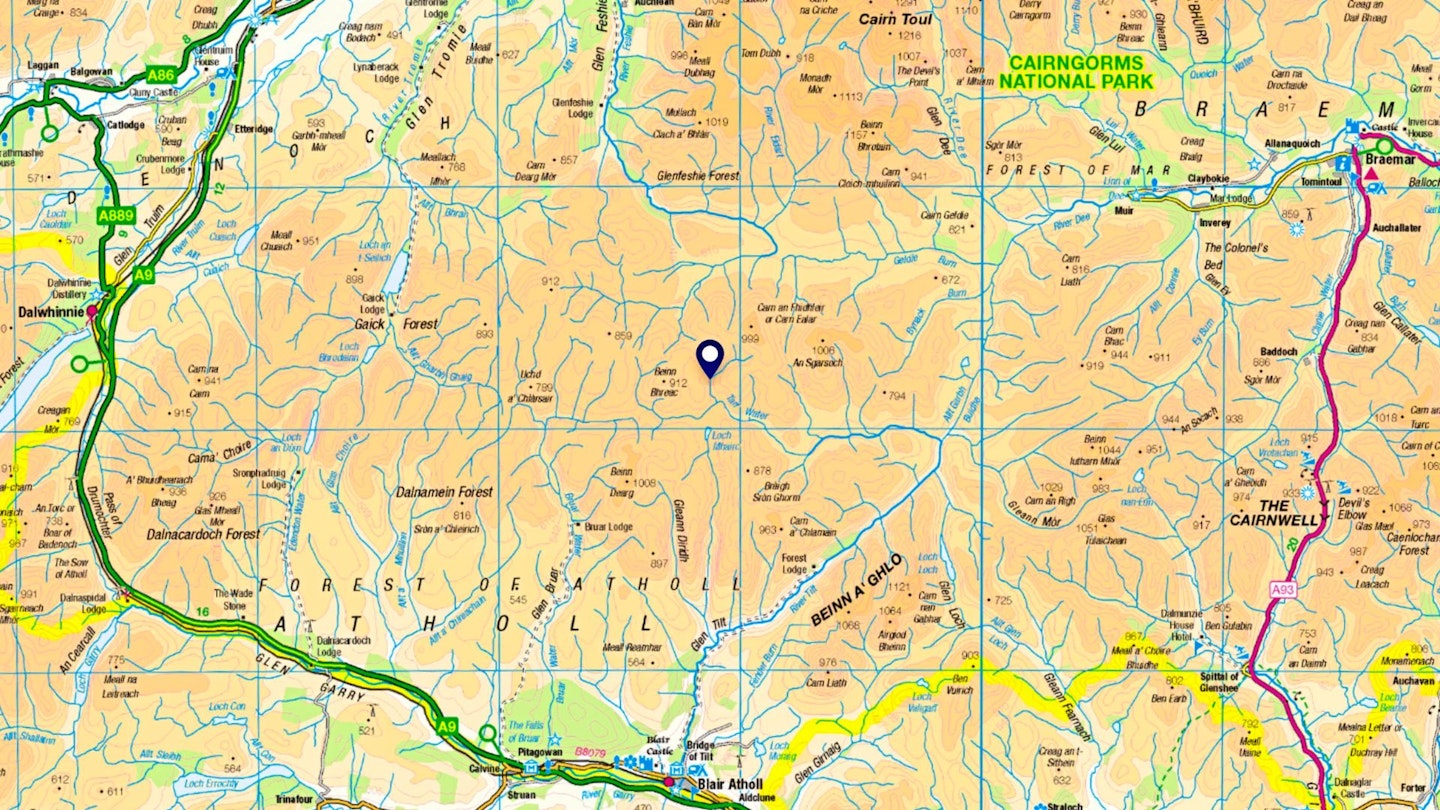

Our long-serving (or should that be long-suffering?) photographer Tom Bailey recently set out on a unique adventure, aiming to find the furthest point in Britain from a public road. The first thing he did was call and ask for help from those clever people at the Ordnance Survey, who delivered him the magical grid reference of NN 88764 82124.

The next thing Tom did was pack his map and compass, update his trusty OS Maps app, charge his phone and GPS watch, then head for the wild and empty landscape of Scotland’s southern Cairngorms. Now Tom is very handy with a map and compass, but he’s also a recent convert to using a smartphone to help pinpoint his exact location for extra reassurance, and OS Maps is his app of choice.

Here's the short story of how he tracked down Britain’s remotest point to a stream in the middle of nowhere – and if you like the sound of it you can read the long version in the September issue of Country Walking magazine.

I left my car in the dappled elegance of a woodland clearing near the Old Bridge of Tilt, which was as close to the remotest spot in Britain as I could park. From here it was 9.9 miles north by crow, further by foot although I wouldn’t know how much further until I’d found my way through the trackless hills.

My journey started on a short section of road, then broad estate tracks which followed Glen Tilt to properties tucked miles up that enchanting glen. Initially, a mixture of evergreen and deciduous trees lined the banks of the deep-cut valley and it wasn’t long before I got to Cumhann-leum Bridge, the first of two that span the River Tilt. The sun was out, birds were singing, and the peaty depths of the river, viewed from my lofty vantage point, seemed almost inviting.

Woodland tracks turned to thin paths as I headed to Ach-mhair Bridge, a leaf-shrouded beauty spanning a deep narrow gorge cut by a tributary to the Tilt. I still shadowed a river – now the Allt Mhairc – up until I reached the New Bridge. It didn’t look very new; more like some part of a medieval castle’s walls. I had arrived in hill country proper and open fells sprawled before me. I crossed the bridge knowing I was about to climb a mountain.

At 2956ft (901m), Beinn Mheadonach is just shy of Munro height – that collection of 282 Scottish mountains of 3000ft or higher. It is a long whale of a peak, swimming pretty much in a north-south orientation, which suited my northwards journey perfectly. Half an hour of climbing and I’d forgotten about the glens. The summit was marked by a column of a cairn pointing defiantly upwards, piercing the air’s insistence, marooned on the plateau of the mountain, far from any edge.

At the far edge of Beinn Mheadhonach’s summit plateau a large vista opened wide and deep, and there, on the limit of what my eyes could make out, was the promised land: the most remote spot in Britain. There was nothing outstanding about it. Low hills squashed and squeezed rivers into indecisive lines, and nothing leapt out at me from the view other than how distant and ‘nothingy’ it all looked.

A northern spur of the mountain lowered me through a maze of small peat hags to the shores of Loch Mhairc. As I looked northwards from the loch, the low hill of Tom Liath barred my way. My legs were tired, so I decided to walk around it. I was eager to see the one obstacle that might stop me in my tracks: a river by the name of Tarf Water.

I followed the course of Tarf Water eastwards, then swung to the north again when a tributary joined. This I followed for the final three-quarters of a mile of the outward journey, swapping banks when I got the chance. The river eventually forked and I crossed the right hand of the two to trace Glas Fèith Mhòr. And when, almost 11 miles after I set out, I hit the outside bend of a meander, I knew from time spent looking at OS mapping that this was pretty much the place.

I ditched my pack, fired up my GPS watch and walked about like some demented ant as I tried to locate the exact location true to the 10-figure grid reference: NN 88764 82124. This represents a 1 metre x 1 metre square. The spot where my GPS said it was lay a few metres from where the OS Maps software had placed it on my computer at home.

GPS devices can be a few metres out, and mine clearly was, but I decided to let it decide where the remotest bit of British soil was – and it put me smack bang in the middle of the stream. As there was no-one around for a good few miles, I did a victory wiggle to claim the spot, like a dog lifts its leg at a lamp post. There were no signs of anyone else having ever visited the location. Long may it be so: there’s power in its anonymity.

How did we find the most remote point in Britain?

There are different ways to define the remotest place in mainland Britain but we asked the Ordnance Survey for the furthest you can get from a public road. The calculation involved terms like polygonise the road network (a method which they discarded as inaccurate) and then GDAL process and rasterising pixels. If you don’t know what those are, you’re not alone, and suffice to say the final coordinates were Easting 288764.13, Northing 782124.17 on the British National Grid, which converts to NN 88764 82124.

The spot lies at the heart of the south-west quadrant of the Cairngorms National Park. A lane 9.0 miles to the south near Blair Atholl is the closest public tarmac, while road end in Glen Feshie lies 9.9 miles to the north, or 11.8 miles to the east at Linn of Dee, or 15.5 miles to the west near Dalwhinnie. You could forge a route from any of those directions, but this is truly wild country: trackless, criss-crossed with rivers that fast become dangerous in rain, and of course, many, many mountains.

Why use OS Maps?

DETAILED ROUTE GUIDES: There are hundreds of thousands of ready-made routes in OS Maps, including every hillwalking route guide we’ve printed in Trail and Country Walking magazines for the past 10 years.

EVERY MAP YOU'LL EVER NEED: Unlimited use of every OS Explorer (1:25k) and OS Landranger (1:50k) map for the whole of Great Britain. That’s 607 maps you can view online, print or download to your phone.

NO SIGNAL? NO PROBLEM: Download maps and routes to your phone so you can use them with confidence wherever you go, even if you’re in the mountains or off the grid with no phone signal.

LOCATE YOURSELF: The new feature Locate Me – successor to the popular OS Locate app – has been added into OS Maps, allowing you to pinpoint your exact location map using a digital compass and detailed grid references

BRING ROUTES TO LIFE IN 3D: Explore anywhere in Britain on your computer with the OS Maps Aerial 3D layer. Fly through routes before you walk them to get a good understanding of the terrain.

PRINT MAPS AS BACK-UP: Print out your own custom routes and maps, so even if your tech fails you’re never stuck without a map. You can choose the scale, orientation and size that suits you.

MOUNTAIN RESCUE ENDORSEMENT: OS Maps is the only navigation app officially recommended by Mountain Rescue – and has been made available to all 47 local volunteer teams in England and Wales.

CLICK HERE to become a Trail or Country Walking magazine subscriber and get 50% off a whole year of digital OS Maps