Sir Chris Bonington, one of the elder statesmen of British mountaineering, was avalanched off the first real mountain he climbed.

He would go on to become one of the foremost climbers of his day, leading expeditions and making first ascents of some of the most challenging and dangerous routes in the world. But, like all of us, he had to start somewhere. And that, for him, was Eryri (Snowdonia), 1952.

Chris was then 16 years old and, lit up by an image of Highlands icon Bidean nam Bian he had come across in a book, he convinced a school friend, Anton, to climb Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon) with him. The pair hitch-hiked to Capel Curig in the New Year, during a particularly hard winter. The hills were drowned in snow, neither had ever climbed before and they were equipped only with their school macs, Chris in a pair of ex-army boots, Anton in his school shoes.

The next day they stood peering at a map in the Pen-y-Pass car park as snow mounted around them and cloud lowered over the peaks. The Pyg Track, their intended route, was almost entirely lost and they were on the point of giving it up when a small group of equipped and competent looking mountaineers arrived and set off. Here was their chance; they followed them up.

“ANTON WAS PUT OFF HILLS FOR LIFE BUT CHRIS WAS HOOKED. HE WOULD SPEND THE REST OF HIS LIFE DEVOTED TO CLIMBING”

Chris and Anton were up to their waists in soft snow, feet numb, and losing sight of the climbers in the billowing cloud when the ground slipped away and took them with it. They emerged, laughing, at the bottom of the slope. It was a minor avalanche, a lucky escape and they returned to the hostel drenched, cold but unharmed. Anton was put off hills for life but Chris was hooked. He would spend the rest of his life devoted to climbing. He was, that day, quite literally swept off his feet.

An emboldened era

In the decades that followed that young teenager would become a high-altitude climber, expedition leader, writer and broadcaster in an era of huge change. When Sir Chris Bonington was born, none of the world’s 8000m peaks had yet been climbed.

The first attempt on the notorious Eiger Nordwand (later nicknamed the ‘mordwand’ for its horrifying death rate) had just been made and a successful summit was still four years away. No-one had ever stood on the Old Man of Hoy. Chris would go on to operate in a group of tough, ambitious climbers; the first generation to make mountaineering a profession.

Tracing his life, from that day on Yr Wyddfa to the celebration of his 90th birthday this year, we see the progression of modern mountaineering. From its rough and simple origins to a global industry and Olympic sport.

When he first started climbing, equipment was limited to a hemp rope around the waist and a pair of hobnailed boots. There were no helmets, no harnesses, no rubberised rock boots. But there were thousands of projects that a keen young climber could apply himself to. One cold and wet, huddled in the corner of a Welsh hostel, dreaming of the next trip.

Mentorship

Christian John Storey Bonington was born in Hampstead on 6 August 1934. Up in north Wales he had had his first experience of the unforgiving mountain environment and shortly afterwards, at Harrison’s Rocks, a small outcrop near Tunbridge Wells, he first experienced the intricacy of climbing. There, searching out holds in the crumbling sandstone, he found what he would call “a complete release in physical expression”.

His apprenticeship to mountaineering was typically, for the time, rough and informal. There were no skills courses or qualifications to work towards, the only recourse for anyone who wanted to learn was to find people who climbed and convince them to take you with them. That Easter, on another visit to north Wales, Chris made an impulsive solo climb up the Idwal Slabs and at the bottom was approached by a teacher who had been watching with two students.

That teacher, Charles Verender, invited him to lead a pitch there and then, giving this relative beginner the responsibility of seeking out the line and securing the rope as he went. Soon afterwards, he put him in charge of instructing one of his students. This kind of mentorship – individual, testing and unregulated – was characteristic of the time and would be all but impossible today.

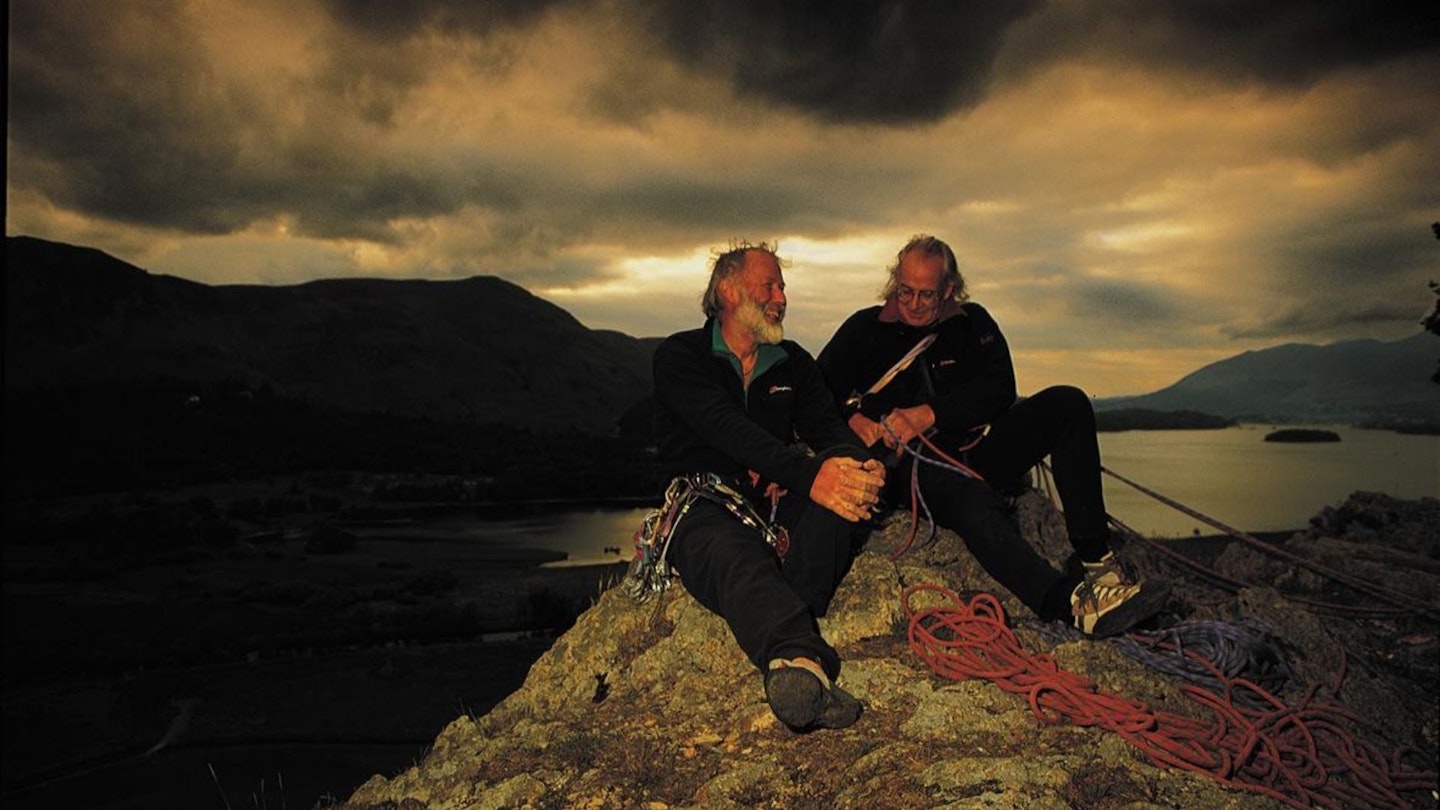

For the next few years, Chris took every opportunity to hitch to Scotland or north Wales, dossing under boulders and climbing until dark. On one such trip, he met Hamish MacInnes, a legendary Scottish mountaineer who would climb winter pitches in his socks if it helped him get better purchase and who later invented the all-metal ice axe. MacInnes simply allowed Chris and his partner to follow as he made a first ascent on a frozen Buachaille Etive Mor.

Prior to this, mountaineering had largely been the purview of the wealthy, who employed shepherds and other landworkers to guide them, but now working and middle-class people had taken it up too. It was cheap, accessible and challenging. A welcome respite to the grind of the working week or a blessed alternative to it. This new group of climbers would go on to become some of the strongest in the world, Chris and MacInnes among them.

The two would go on to climb regularly together and it was in MacInnes’ company that Chris made his first trip to the Alps. Their objective: the Eiger Nordwand.

The high mountains

At the time, 14 people had died trying to climb the North Face of the Eiger and only 12 people had made it to the top. Chris would successfully climb it four years later but that year bad weather sent he and MacInnes off the face, so instead they set a new route on the 3444m Aiguille du Tacul. There, Chris had his first experience of exploratory climbing in big mountains. All the elements of the work he loved – the stark mountain environment, the complexity and physical challenge, the freedom of exploration – had come together.

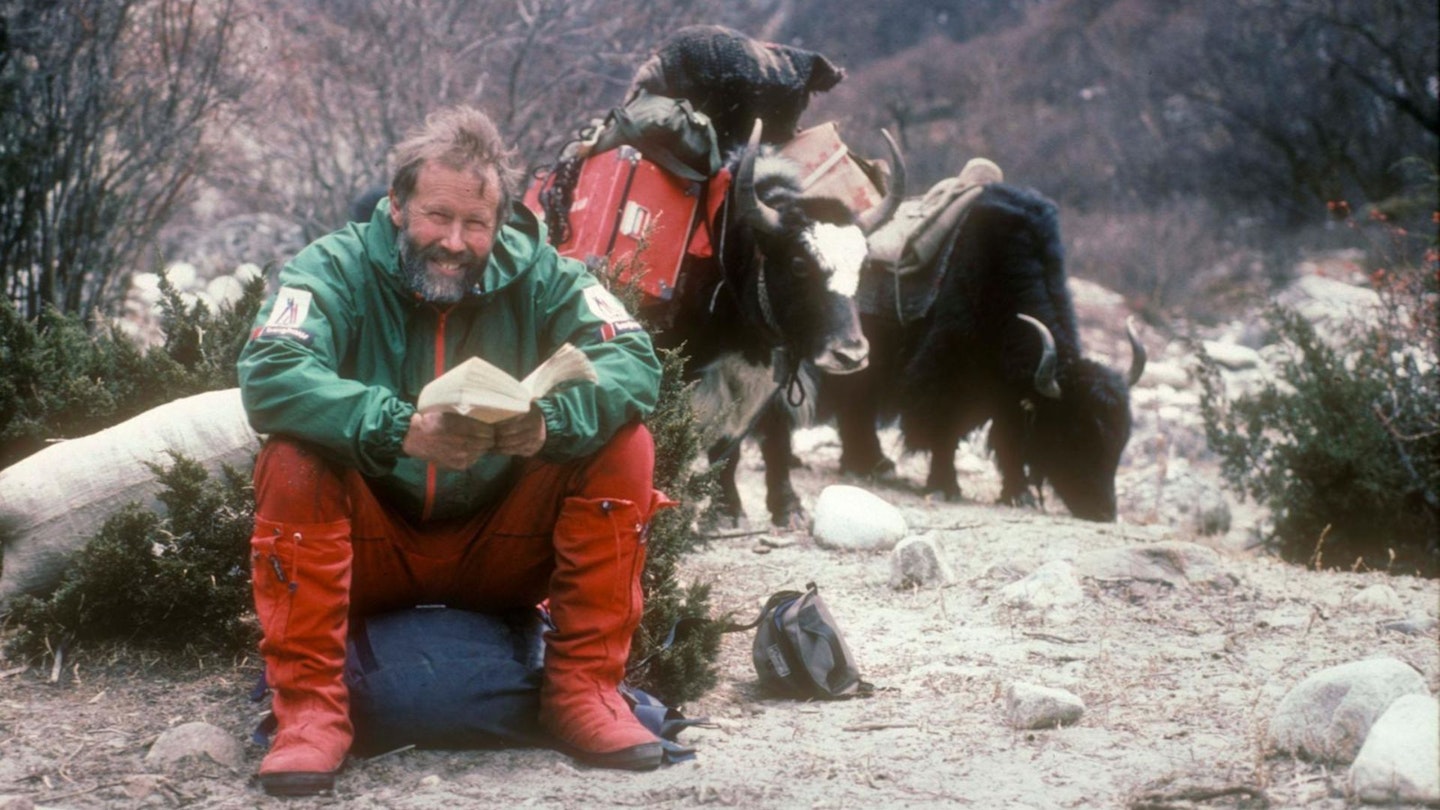

In 1960, he would go higher still – to the Himalayas on a joint British-Nepali expedition aiming to climb Annapurna II. Nepal only opened to western visitors in 1951 and the first 8000m peak had been climbed just one year before, when an expedition led by Maurice Herzog made it to the top of Annapurna in 1950.

Now, the Annapurna circuit is one of the most popular trekking routes in the world (15,900 people walked it in 2022) and Pokhara is just a short flight from Kathmandu. Back then however, getting there required a boat to Mumbai, train to Kathmandu and then a 16-day trek to their base camp at Manang. On May 17, with Ang Nyima and Dick Grant, Chris sat on the summit at 7937m, the landscape below awash in clouds.

Making it work

Through his young adulthood, Chris would try to support himself first with a job in the military, then as a trainee margarine salesman but the media presented new opportunities. The British media, still thrilled by the 1953 Everest expedition, in a country still trying to piece its identity back together after the devastation of WWII and the collapse of the Empire, was hungry for tales of derring-do. There was also a new outlet for storytelling: the telly.

In 1962, Chris and Ian Clough made headline news by getting to the top of the Eiger Nordwand.

“WHEN HE WAS BORN NONE OF THE WORLD’S 8000M PEAKS HAD YET BEEN CLIMBED… NO-ONE HAD EVER STOOD ON THE OLD MAN OF HOY”

Suddenly Chris had offers: people wanted to hear about it, read about it, see pictures of it. Several new income streams in writing, photography and lecturing came together to create a new kind of freelance employment that would sit neatly alongside his climbing and that same year he quit his job to pursue it full-time.

In an example of how well this worked, less than a year after making the first ascent of the Old Man of Hoy with Tom Patey and Rusty Baillie, Chris and Tom returned to climb it again. This time the whole thing, with a larger team and two new routes, was filmed for a three-day BBC broadcast watched by 15 million people.

Taking the lead

Chris’ first role as expedition leader came in 1970, borne not so much from a desire to take charge as to make sure that a dreamed-of expedition – the south face of Annapurna – actually happened. It did, that May, when, supported by a climbing team of six, Dougal Haston and Don Whillans reached the summit.

There would be many more, including the summit of Everest via the south-west face in 1975. Between 1950 and 1964, all the 8000m peaks were climbed but the appetite for ambitious routes was far from sated. There were still numerous hard lines to try or terrifying summits to reach. Tinkering had been a part of climbing since the very early days, when hardware was fashioned from nuts scavenged from the factory floor, and it was progressing into an industry.

The very climbers who were attempting these hard routes were trying to find ways to make it easier, safer or more comfortable, and as a result equipment and clothing had changed significantly.

There were now webbing harnesses, nylon ropes and down suits. When Doug Scott and Dougal Haston walked onto the summit of Everest on 24 September 1975, just as the sun set, after climbing the southwest face, they were wearing the first ever down suits, designed by Pete Hutchinson and Don Whillans specifically for the expedition.

Over the following decades Bonington would continue to lead expeditions around the world and take a more official role in gear development when he started working alongside Berghaus. Mountaineering would go on to become a commercial interest and guiding in the hills a legitimate career choice. Much has changed since he first started climbing but the lure of those places has not. If anything, the only thing that has changed is that more people feel it.

This year, Chris celebrated his birthday with a walk up his favourite local fell, High Pike, with family and close friends. At 90 years old, still fit, still finding joy in high places.

This route originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Trail magazine. CLICK HERE to become a Trail magazine subscriber and get 50% off a whole year of digital OS Maps.